Many of us Boomers grew up with chess sets in the house. Many of these were cheap plastic jobs imported from Japan. Some of us had prestigious cast or carved versions. But odds are that all of us, when sitting down to take on one of our youthful opponents, fancied ourselves to be the great Bobby Fischer, the world’s household name among competitive chess players of the 60’s and 70’s.

The first competitive chess tournament whose winner would be declared Europe’s best player took place at London’s Great Exhibition of 1851. Of course, you were aware that it was Adolf Anderssen who won, with accusations of unfairness by a defeated player, Howard Staunton.

I know, you never heard of them, but it’s interesting that the very first competition would be marred by the same controversies that would dog the sport throughout the 20th century.

For many years, it was Germany who spawned chess champions. In 1921, Cuban José Raúl Capablanca began a reign which lasted for eight years. He was eventually deposed by Alexander Alekhine, a French-Russian who would be a harbinger of the future of chess and its domination by those blasted Commies.

On October 17, 1956, a thirteen-year-old named Bobby Fischer took on master player Donald Byrne and defeated him in what a chess publication called “The Game of the Century.” Perhaps it was, but few outside of the chess community were aware of it.

That was about to change.

Fischer’s chess playing days began in May, 1949, with a set bought at a Brooklyn candy store. The six-year-old and his sister had to read the enclosed instructions to learn how to play. Fascinated with the game, Bobby began reading books documenting old games in order to digest the strategy involved. In 1951, eight-year-old Bobby began frequenting the Brooklyn Chess Club, where his education continued to be fed by master players. He joined other New York City clubs before his victory against Byrne put him on the map as one of the world’s elite players.

Two months shy of his fifteenth birthday, Fischer became the youngest US Champion in chess in 1958. The timing of the tournament also gained him the lifetime title of International Master.

Chess has a biannual tournament called the Olympiad, which is held in different countries. The US was a sporadic participant prior to the rise of Fischer, but he represented his country in matches in 1960, 1962, 1966, and 1970. His best finishes were silver in 1960 and 1966. The latter match took place in embargoed Havana, and Fischer was forced to play remotely, adding time delays as moves were communicated back and forth. This no doubt added to the pressure as he came up just short of winning the whole shebang.

In 1960, Fischer lost the championship match to Boris Spassky at the Mar del Plata (Argentina) tournament. Despite a strong dislike for Russian communism, he became lifelong friends with his rival Spassky.

As it would turn out, Fischer’s matches with his friend would be legendary, and would capture the world’s attention like the game had never before done in its history.

Fischer began competing in Candidates Tournaments, which would determine the players for the World Chess Championship. He had become famous enough by 1962 that Sports Illustrated interviewed him after losing out in that year’s competition at Curaçao. He accused the Soviets of playing to draws so that they could save their energy to concentrate on him. He claimed that the format of the tournament made Soviet collusion impossible to stop, and announced that he would never play in one again. The World Chess Federation was listening, and replaced the tournament format with a one-on-one situation that would make collusion impossible.

Thus, the door opened for a single talent to overcome a nation of talents.

However, Fischer didn’t take advantage right away. Instead, he concentrated on US tournaments and exhibitions. His fame grew, and earned him a profile and a cover picture on LIFE magazine in 1964. Sports Illustrated also did another feature article on his mowing down the opposition in that year’s US Championship.

However, Fischer didn’t take advantage right away. Instead, he concentrated on US tournaments and exhibitions. His fame grew, and earned him a profile and a cover picture on LIFE magazine in 1964. Sports Illustrated also did another feature article on his mowing down the opposition in that year’s US Championship.

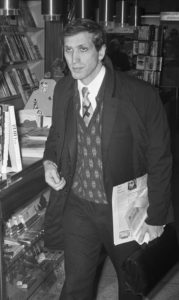

In 1970, Fischer decided the time was right to go for the World Championship. He had achieved enough fame in the US that the media payed close attention as he began his quest. He competed in many big-name tournaments where doing well would get him to the big Championship match of 1972. He won often, and became a common name in the sports pages, a place unaccustomed to reporting on chess.

Fischer made it to the Big Show, and it came down to him and his pal Spassky at Reykjavik, Iceland. The matches went on from July to September, and ABC’s Wide World of Sports was there to show it to us breathless Boomers and our parents.

Finally, Fischer defeated his Russian opponent, and the first United States World Chess Champion began his reign. The US media went nuts, and Fischer was offered (and turned down) millions of dollars for endorsement deals. He did appear on TV, though, particularly on one Bob Hope special with Mark Spitz.

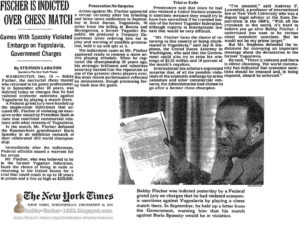

In 1975, Fischer failed to show up to defend his title, beginning a long withdrawal from the public eye. In 1992, he played his friend Spassky again in Belgrade, Yugoslavia in an exhibition match which earned him the wrath of his country. Yugoslavia was under a UN embargo (supported by the USA), and this match put him in direct violation of it. Prior to the competition, Fischer held a press conference and literally spit on the order that forbade him from participating.

After defeating Spassky yet again, he was now forced to live outside the US, or else face the legal consequences of his actions. He disappeared from public view again, and died in January 2008 in Iceland.

Fischer leaves a legacy of brilliance, obstinance, eccentricity, and some unfortunate anti-Semitic remarks, particularly painful to hear in the light of his mother being Jewish. He even wrote a friendly letter to Osama Bin Laden days after 9/11/2001, comparing their estranged statuses from the US and their shared hatred of Jews. Ecch.

But lest we forget, he was once the toast of the country. he also managed to put the pastime of chess firmly into the public eye, and that legacy will, it is hoped, outlast the decisions he made late in life.

BTW, if you haven’t seen it, I heartily recommend watching Searching for Bobby Fischer. It’s a warm movie that will leave you feeling good.