I have the 1968 St. Louis Cardinals to thank for getting me into baseball. I grew up with dad listening to the games on KMOX every night during the summer, but I didn’t start paying attention until that fateful series that the Cards lost in seven to Detroit (ah, revenge is sweet ;-).

I have the 1968 St. Louis Cardinals to thank for getting me into baseball. I grew up with dad listening to the games on KMOX every night during the summer, but I didn’t start paying attention until that fateful series that the Cards lost in seven to Detroit (ah, revenge is sweet ;-).

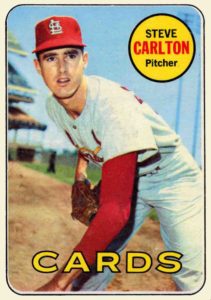

The next year, I was eagerly grabbing up packs of baseball cards from the little store that sat next to my grade school, White Rock Elementary at little Jane, Missouri.

Each morning, after the school bus deposited me at the school’s back door, I would hike across the schoolyard to the store.

A nickel bought a treasure trove: about ten cards (as I recall) and the world’s hardest flat stick of bubble gum.

As it turned out, the cards WERE a literal treasure trove, if you were farsighted enough to stash them away in their original mint condition.

As it turned out, the cards WERE a literal treasure trove, if you were farsighted enough to stash them away in their original mint condition.

Yeah, right. A nine-year-old is going to do THAT.

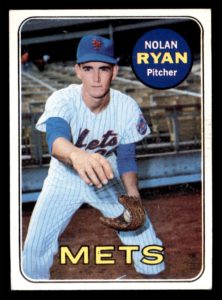

The morning ritual involved unwrapping your purchase and looking for those elusive missing cards that your collection needed. More often, you would get dupes of cards you already had. The pictured Nolan Ryan 1969 issue was one that I had at least five of.

They now go for $200 and up in mint condition on eBay, BTW.

But you used your dupes as traders, to swap with fellow collectors to get the ones that you just couldn’t find in those store packs.

I seemed to hit a wall with the Cardinals. Though I had multiple Steve Carltons (also very valuable today), I just couldn’t ever find a Bob Gibson. A trip to Texas revealed why.

I seemed to hit a wall with the Cardinals. Though I had multiple Steve Carltons (also very valuable today), I just couldn’t ever find a Bob Gibson. A trip to Texas revealed why.

We ventured down to the small town of Mason, located near the geographical center of the state. That’s where my grandparents lived, and we made yearly sojourns to their home.

Anyhow, I walked into a store there and bought a few packs of cards. I was astonished to find out that they were a completely different distribution from what I was buying back home! Within four or five packs, I had found TWO Bob Gibsons! The rest of the cards were all elusive ones I’d never been able to find.

While I was thrilled, I also became cynical. After all, I soon realized that my collections would never be complete without a trip out of the state.

That was my first and last year collecting baseball cards. I did become a collector of football cards, and even collected NBA cards for one year. But I was alienated by Topps, who, for whatever reason, didn’t distribute their entire inventory to each geographical area.

Had I kept my collection in mint condition, it would probably be over a thousand dollars in value today, not bad for an investment of perhaps ten bucks. I’m not sure what happened to them. I know many of them were clipped to my bike to rub against the spokes to make a motorcycle sound.

But for at least one year, I was able to wow my father by quoting statistics for the players we would see on NBC’s Game of the Week each Saturday afternoon.