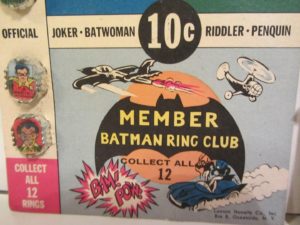

Circa 1966, opening a box of cereal, or a box of Cracker Jack, or one of those plastic egg-shaped containers from a gumball machine would often reveal a plastic ring that magically made an image transform before our very own seven-year-old eyes! It was amazing, high-tech stuff that epitomized the technological age we were living in.

The rings were cheap, simple, and a hit with kids. Nowadays, originals are no longer cheap. The technology behind them was also far from simple. But Chinese-made flicker rings continue to be a hit with the latest crop of kids.

The flicker ring traces its roots back to the late 1930’s. A company called VariVue (or Vari-Vue, they appeared to use both names) began marketing a technology called lenticular images. The idea behind them was that two or more distinct images were placed under a plastic lens which had been very precisely cut with parallel slits. These slits would allow the eye to see one image at a time, and as the object was moved slightly, a different image would appear.

The result was apparent motion. It was decidedly cool.

VariVue began marketing their lenses and technology to advertisers, and flicker images began appearing on signs and billboards. By the time the 50’s arrived, you could see flicker images on pin-on buttons, post cards, book covers, and advertising giveaways.

Of course, another popular use of flicker technology was in magically transforming voluptuous young ladies from states of dress to states of undress. Of course.

You probably recall little flat pictures found inside Cracker Jack and cereal boxes. These were popular, but it was the rings that many of us remember the most fondly.

The rings were sported by Boomer kids all over the world. They were typically brightly colored, and featured characters from cartoons, comic books, and TV shows. I know that I had rings that depicted Batman, Superman, and various Looney Toons fixtures.

Flicker rings are still out there, to be sure. Today’s children continue to enjoy them, as have every generation since the 1950’s, but let’s face it: they don’t hold the same magic.

How could they? We grew up in a time when computers cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, and required large climate-controlled rooms for their operation. The closest thing we had to the internet was the public library. We were coming to terms with seeing TV images in color, not comparing the merits of 1080i vs. 1080p HD resolutions.

But still, it gives me a good feeling knowing that a generation of six-year-old kids is proudly wearing flicker rings, perhaps even bearing moving images of Batman, Superman, or a Looney Toons character.