We Boomer kids had a few constants in our lives growing up, some good, some bad. There would be coverage of the Vietnam War every night on the news. Dad would install a new license plate on the car every January. And Lucille Ball would have a hit television show.

We Boomer kids had a few constants in our lives growing up, some good, some bad. There would be coverage of the Vietnam War every night on the news. Dad would install a new license plate on the car every January. And Lucille Ball would have a hit television show.

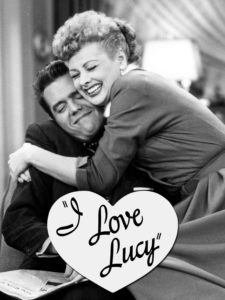

Lucy was best known, of course, as Lucy Ricardo, beloved bride of Ricky, in a show that is ranked as the most popular ever by many. I Love Lucy ran for seven seasons beginning in 1951, and the duo went three more years on The Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour. And just because you were too young to catch it the first time didn’t mean you had to miss it. The first series to be filmed in the studio, instead of being broadcast live, Desi and Lucy shrewdly gained all rights to the show after production ceased, meaning they made untold millions licensing it for syndication.

It’s nice when the artists win, instead of the executives.

Anyhow, it is unlikely that a single Boomer in the US has never seen an episode of I Love Lucy. To this day, it remains of of the most popular syndicated shows on television.

But just because I Love Lucy sailed off into the prime time sunset didn’t mean Lucille Ball was done with television. Far from it.

In 1962, Lucy, now amicably divorced from Desi, began starring in The Lucy Show. It was a perennial ratings giant for CBS, and starred Lucy’s buddies Vivian Vance and Gale Gordon, who played the constantly angry Mr. Mooney. Gordon was the first pick to play Fred Mertz on I Love Lucy, but was committed to another series (Our Miss Brooks) at the time. However, he did make some guest appearances. When Lucy was offered her new show, Gordon was immediately selected to play the part of Banker Mr. Mooney.

Wouldn’t you know it, he was committed yet again to another series, this time playing Mr. Wilson on Dennis the Menace. But by the show’s second year, he was available, and he replaced a previous banker character played by Charles Lane.

Lucy’s own Desilu Studios produced the show, so Lucy was the show’s boss. When she sold out to Gulf and Western Industries in 1967, she decided she didn’t want to work on a show over which she no longer had full creative control. So The Lucy Show disappeared, to be immediately replaced by Here’s Lucy.

Here’s Lucy starred Gordon, Mary Jane Croft (who had assumed the role of a best friend for Lucy after Vivian Vance’s 1965 departure), and, of course, Lucy herself.

The show featured all new characters, but the audience had a hard time telling them from the former ones. They had different names, but as far as were concerned, it was still Mrs. Carmichael and Mr, Mooney. And Lucy, of course, still called the shots.

Here’s Lucy was as popular as the previous show, consistently landing great ratings until 1974, when its popularity sagged just a bit. At this point, what happened is not exactly clear. Either Lucy herself declared that a great show had run its course, or CBS pulled the plug on the last old-style comedy of the 60’s to enhance its reputation of taking bold new moves with shows like All in the Family. Either way, it was still in the Top Thirty when it was canceled.

So for the first time in memory, Lucy was not on television every week.

Lucy and Gale Gordon tried a 1986 comeback, Life with Lucy, but by then the humor formula of the old shows no longer worked. I recall it having the same premise as her two previous shows, just with everyone having gotten a lot older. I think it would have been a success had it been released in the 60’s. Two short months after its debut, it was gone.

Nowadays, the very concept of the sitcom has been largely shove aside. Long-running shows like Everybody Loves Raymond, The King of Queens, and Friends are quite rare. Something called reality TV has unfortunately proven popular, with numerous clones of the (IMHO) disturbing genre getting high ratings.

Ah, for a simpler day, when you could count on Lucy and Mr. Mooney to be on TV reliably every week.