You want to hear something weird? While pondering column ideas this morning, the thought of Buddy Holly popped into my head. Being a Don McLean fan, I thought “why not write about the the day the music died?” So I set out to go to work.

You want to hear something weird? While pondering column ideas this morning, the thought of Buddy Holly popped into my head. Being a Don McLean fan, I thought “why not write about the the day the music died?” So I set out to go to work.

It was after I had invested a half hour of my time that I finally realized that the infamous plane crash occurred 49 years this very day (Feb. 3, presstime).

Strange, wouldn’t you say?

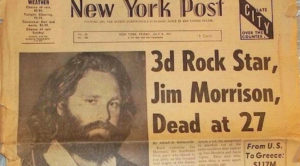

Anyhow, rock and roll music, still in its infancy, received a shot in the arm of pure immortality that unfortunate day so long ago when three talented musicians, as well as a pilot, gave up their lives in a frozen Iowa cornfield. Many of us were too young to remember it, but the genre, which might have passed the way of other musical crazes, was cemented in place as the voice of not only the current generation, but that of future ones as well.

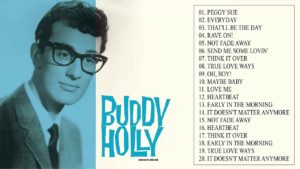

Buddy Holly, inspired by seeing Elvis perform live in 1955, began playing clubs in hometown Lubbock, Texas shortly afterward. Within a few months, he appeared on Presley’s bill during a tour stop in Lubbock. Soon, he was cutting records at Norman Petty’s studio at Clovis, New Mexico with his newly formed backup group, The Crickets.

Artists have long been exploited by music industry fatcats, and Holly was no exception. Petty tried to muscle in on Holly’s royalties by claiming to be a cowriter of his lyrics. This was a fairly common practice among producers at the time. Well, Buddy got tired of it and moved to New York.

Litigation took place between Holy and Petty, and the artist felt a cash crunch. So the wildly successful musician agreed to take part in the Winter Dance Party Tour just so he could pay the bills.

In the meantime, Ricardo Valenzuela, born in California, had found an ear for his Latino-tinged brand of rock and roll. La Bamba, a traditional song, was a massive 1958 hit when the artist, now known as Ritchie Valens, belted it out. When he got invited to join the Winter Dance Party Tour, he jumped aboard.

Jiles Perry (J.P.) Richardson, Jr. was a successful disc jockey who was imbued with musical talent himself. He wrote a song called White Lightnin‘ which turned out to be a #1 hit for George Jones. He also wrote a novelty hit called Running Bear which was one of my favorite songs when I was a kid.

In 1958, he recorded a song he had written called Chantilly Lace. He had previously invented a DJ-singer persona called The Big Bopper, and that’s who was credited as the song’s performer. The song peaked at #6, and The Big Bopper also said yes to the 1959 winter tour.

Dion and the Belmonts also joined up, and the tour was on its way.

It was the dead of winter, and the buses used to transport the artists had no heat. Drummer Carl Bunch ended up in the hospital with frostbitten feet. Disgusted, Holly chartered a plane to fly from Clear Lake, Iowa to Fargo, ND. The single-engine Beechcraft Bonanza had room for three passengers, and after begging, cajoling, and coin-flipping had taken place, the seats were occupied by Holly, Valens, and The Big Bopper.

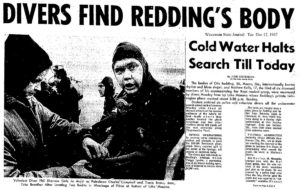

The plane crashed shortly after takeoff, and, for better or worse, legends were born.

Holly was amazingly prolific during his short time. He wrote and performed nearly a hundred songs in two years, and many have been re-recorded by artists hundreds of times. One wonders what he, as well as Valens and The Big Bopper, might have accomplished with just a little more time.

By the way, if you find yourself in Vegas, stop in at the Hard Rock cafe to see some amazing candid color photos of Buddy.